Background: Despite increasing calls from programmers, researchers, and community advocates for gender transformative programs to systematically incorporate intersectionality as a core principle, program implementers and gender advocates still grapple with how best to integrate intersectional considerations in their efforts to advance gender equality for all individuals.

Event Overview: The Interagency Gender Working Group (IGWG) hosted a gender knowledge exchange event on June 20 from 8:00–10:00 a.m. EDT to explore approaches to understanding intersectionality in gender transformative programming in global health.

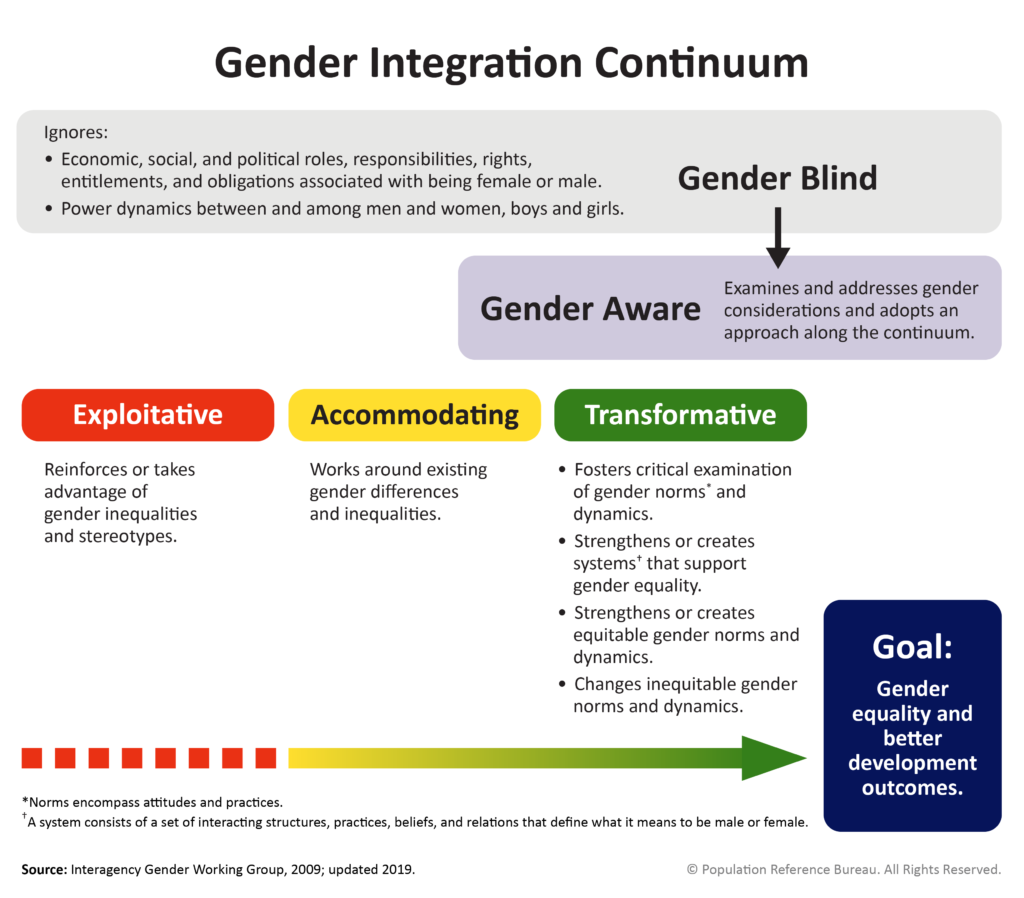

Although gender is widely understood in public health settings as a fluid concept that incorporates behaviors, expressions, roles, responsibilities, identities, relations, norms, and institutional practices, many program interventions miss the mark in addressing the vast array of lived experiences across the diversity of people affected by gender bias, discrimination, and violence. Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, the term intersectionality illustrates the effects of overlapping systems of discrimination, such as those based on gender, race, class, sexuality, and other identities. Program implementers, researchers, and advocates can improve their understanding of historical structural inequalities and power dynamics across a range of issues that intersect with gender—and improve health and gender outcomes—by applying a wider intersectional lens to gender transformative programs and health interventions.

This gender knowledge exchange provided IGWG members with the opportunity to hear lessons learned from gender champions and experts on intersectionality in a small-group setting. The event began with a panel discussion led by a group of experts, advocates, and researchers focused on strategies for and approaches to intersectionality in gender transformative health programs and research aiming to advance gender equality outcomes. Attendees then joined breakout rooms to ask questions and share their insights.

Panelists included:

- Njeri Kimotho (she/her), Global Gender and Social Inclusion, Intersectional Feminist, Gender Equality & Social Justice Lead, Solidaridad Network, Kenya

- Doose Didi Mchihi (she/her), Founder/Chief Psychotherapist, The WellBeing Center, Nigeria

- Dr. Lata Narayanaswamy (she/her), Associate Professor, University of Leeds, United Kingdom (moderator)

Event Recording

Key Takeaways

What is intersectionality—and what is it not?

- Intersectionality is a lens and approach to understanding how humans experience the world in the systems and environments around them. Gender champions should apply both gender and intersectional analytical lenses, recognizing that individuals have multiple identities and may identify in different ways depending on the environment and experience different inclusions, exclusions, and barriers. No person experiences one single struggle.

- Intersectionality is about more than identity; it is not a checklist of identities. By integrating an intersectional lens, program implementers can better understand how their implementation efforts are producing privileges, marginalization, and other effects.

- Intersectional approaches should meet people at their points of need. Intersectionality means recognizing individuals’ economic barriers, health care accessibility, and other issues, and designing programs that incorporate these holistic issues. For example, consider a woman living with a disability in Nigeria who might be responsible for raising children without a partner—using an intersectional lens and recognizing how her multiple identities influence her lived experience, what needs might she have that program implementers should consider in program design?

What are opportunities for intersectionality in gender transformative programming, and why is intersectionality important?

- When applying an intersectional lens, program designers and implementers should aim to understand the unique challenges and identities of the groups they are working to reach. For example, intersex women face many issues, such as violence and discrimination. We must recognize these issues to adequately design programs to address them. The LGBTQ+ community experiences structural barriers influenced by their sexual orientation. Implementers should aim to break down these structural barriers to achieve comprehensive outcomes in program design. Project design should be oriented around voices that are not typically heard. Intersectionality means reaching groups that are not often reached by mainstream programs.

- Program implementers must change how gender analyses are conducted. Intersectionality provides a new lens to ask different questions, taking a research or problem-solving approach. Intersectionality encourages the consideration of greater nuance of insights about how people experience the world and interact with systems and policies. To do so, program implementers must check their own personal biases, starting with acknowledging gaps in their own knowledge. This process also requires program implementers to acknowledge their own intersectional identities.

What have you found challenging for program implementers when applying intersectionality in your work?

- A gender analysis is often an assessment conducted by external experts. It has not always incorporated an explicit requirement to check personal implicit biases as part of the process. The step of assessing and addressing implicit biases as part of an intersectional lens has been a challenge in program implementation. Similarly, bias within program staff (for example, misogyny, homophobia, racism, and classism) needs to be addressed. Intersectionality challenges program implementers to question their understanding and experiences and to incorporate open-ended questions.

- One challenge program implementers face is resistance from policymakers and stakeholders. Doose Didi Mchihi discussed how she addressed such resistance while launching a life planning program in northern Nigeria for adolescents and youth surrounding sexual and reproductive health and scaling up the availability of contraceptives. Program implementers understood that the program was being implemented in a region where religion has a strong influence. The program saw high rates of forced child marriage. Existing power dynamics made it difficult for married adolescent girls to participate in the program. Because some husbands and fathers were not allowing girls to attend program activities, implementers realized they had to include men, boys, and religious leaders in the program. Doose described that the team had to stop and re-strategize during the implementation. They asked other civil society organizations that were already established in the area to help and invited input from relevant stakeholders within those communities who were able to share strategies that would be culturally accepted. After incorporating stakeholder input, implementers developed programs that were culturally responsive, and thus achieved desired outcomes.

- The expected outcomes of intersectional approaches are often not reflected in the levels of funding allocated for these approaches. Many gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) teams integrate gender into very large programs with no budget lines. Transformative intersectional work requires adequate funding.

- Programs should seek partnerships with movements, such as feminist and women’s rights movements, LGBTQ+ movements, and movements by racial and ethnic minority groups. Large-scale change is impossible without movement efforts.

How do you apply an intersectional lens in program design and intervention in gender transformative health programming and advocacy? Do you have any examples of what worked well or lessons learned? How do you manage risk in programs?

- It is important to invite people from the communities that programs are targeting to speak about the issues affecting them, as well as to be involved in program design and implementation. In Nigeria, the LGBTQ+ community has been able to design capacity-building training for people within the community. Speaking on her work with the LGBTQ+ community, Doose shared an approach that she has seen work at the grassroots level is to start from the health and human rights angle, then discussing topics, such as sexuality, that may be considered sensitive. Recognizing that within the LGBTQ+ communities in Nigeria, there are people who are sex workers, people who use drugs, and people with other marginalized identities, questions program implementers working in these contexts should consider when designing programs include: Do you feel comfortable doing this? Do you feel safe? Are there any risks?

What other factors should program implementers and designers and researchers consider for incorporating intersectional approaches in their work?

- Program implementers should invite communities to plan programs and strategies from the beginning of programming, as well as find ways to question their assumptions about what is important.

- Programs should incorporate a learning agenda. Learning does not necessarily mean collecting data points; it also means listening to communities. During assessments, midterm, or evaluations, program implementers can incorporate qualitative data collection and analysis, as well as leadership by community members. In such assessments, implementers should question whose knowledge is being produced. It is important to move beyond the individual approach to see how programs have a ripple effect on communities at large.

How have you balanced the integration of various intersectional issues?

- Njeri Kimotho shared how she approaches intersectional social relations assessment as research. Adopting a research angle, she starts with a problem analysis and then identifies who is most affected by that problem: men or women? Boys or girls? Age brackets? Different religious groups? It’s important to be very specific in identifying who the program will target. Starting with the problem provides an opportunity to have a more in-depth discussion with the correct people and determine who the problem is truly affecting. Implementers should remember that some people may want to be part of a project while not actually being impacted adversely by the problem at hand.

- Implementers should consider conducting needs assessments, as well as incorporating a focus group discussion with the range of people the program is targeting to identify the problems that need to be addressed immediately. Needs assessments allow implementers to identify priority areas and then channel resources toward solving relevant problems.

Explore Additional Resources

Reading Resources:

- A Study on Intersectional Approaches to Gender Mainstreaming in Adaptation-Relevant Interventions (Adaption Fund).

- Intersectionality: Reflections from the Gender & Development Network

- Using Intersectionality to Better Understand Health System Resilience [Resilient & Responsive Health Systems (RESYST)].

Application Tools:

- Intersectionality Resource Guide and Toolkit (UN Women).

- Introduction to the Power Matrix (Valerie Miller).

- Gender, Inclusion, Power and Politics (GIPP) Analysis Toolkit (Christian Aid and Social Development Direct).

Case Studies: