This blog was developed by Francesca Alvarez, Alyssa Bovell, Emily Clark, Joy Cunningham, and Maia Johnstone based on content shared through a recent event hosted by the IGWG Gender-Based Violence Task Force.

Event Overview

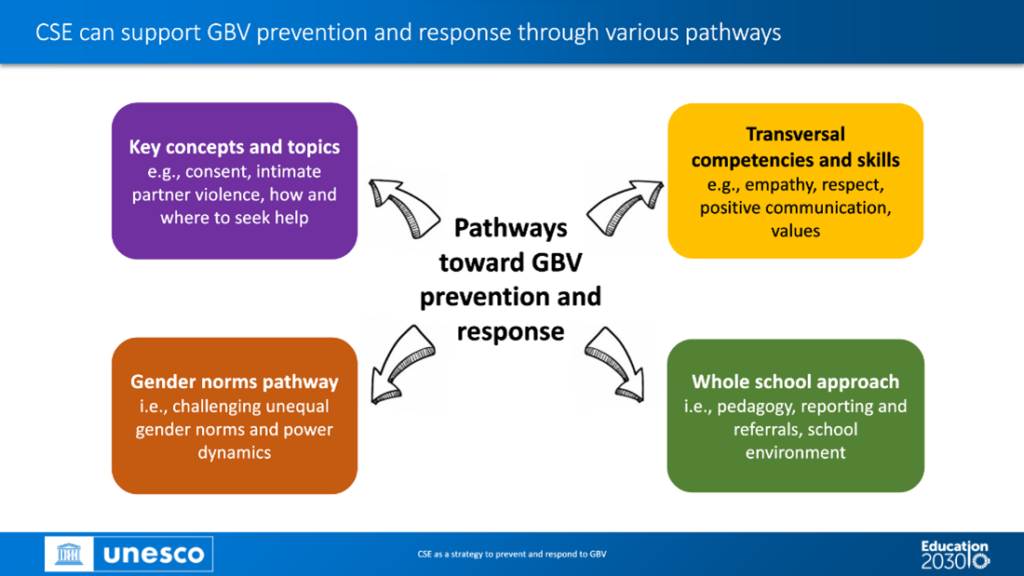

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is backed by three decades of empirical and scientific evidence and is linked to health outcomes including delayed sexual debut, reduced risky health behaviors, increased use of contraception, and reduced gender-based violence (GBV).1 Evidence has shown that early intervention may help prevent children from perpetrating violence and recognize that violence is unacceptable.2 Additionally, interventions encouraging critical reflection on gendered social norms show promise for helping to prevent intimate partner violence among young people.3 While the relationship between CSE and GBV requires further exploration, some researchers and experts have noted the potential for CSE to contribute to long-term health improvements, reduce GBV, reduce discrimination, and strengthen gender equitable norms.4 5

On December 5, program implementers, researchers, and policymakers came together for a virtual learning event, Examining Comprehensive Sexuality Education in Gender-Based Violence Prevention and Response Efforts. The event also coincided with the 2023 16 Days of Activism Against GBV campaign. The 90-minute discussion explored linkages between GBV programs and CSE, provided an overview of UNESCO’s International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education, and highlighted existing evidence, lessons learned, and promising practices. Read on for insights on the challenges from this work, evidence-based programming from across the globe, future opportunities for the field, and resources to support program implementers and advocates in advancing these efforts.

Event panelists included:

- Dr. Avni Amin, Technical Officer, Violence Against Women, WHO (moderator)

- Shamah Bulangis, Co-chair, Transform Education, Philippines

- Sheena Hadi, Executive Director, Aahung, Pakistan

- Dr. Remmy Shawa, Senior Project Officer- Health Education, UNESCO, South Africa

- Jeannie Ferreras Gómez, National Programme Officer Gender and Youth, UNFPA, Dominican Republic

Linking GBV and CSE

Avni Amin began the session by highlighting what is known about what works to prevent GBV, citing the RESPECT Women: Preventing Violence Against Women framework developed by WHO and UN Women, which contains seven prevention strategies. Two of those strategies, making environments safe and preventing child and adolescent abuse, reflect where CSE programming is situated and have the potential to contribute to robust GBV prevention efforts. Amin emphasized that in order for CSE programming to contribute to GBV prevention outcomes, it must maintain fidelity to core guiding principles for effective GBV programming; have an explicit theory of change; consider the duration and intensity—or dose—of prevention strategies within the intervention (such as nonviolent conflict resolution and challenging harmful gender beliefs, attitudes, and norms over a period of time); and prioritize the skills and training of implementers to integrate GBV interventions within CSE programming. She also noted a critical gap: the need for further evidence on the effectiveness of CSE in contributing to violence prevention outcomes.

Next, Remmy Shawa provided an overview of UNESCO’s International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education (ITGSE), highlighting ITGSE concepts that can be linked to addressing GBV. CSE includes skills to develop healthy relationships, develop knowledge around gender and GBV, and address inequitable relationships and harmful attitudes, beliefs, and norms that can perpetuate violence. He provided examples of GBV-related content in the ITGSE broken down by age group, including age-specific help-seeking guidance for individuals experiencing GBV. Shawa emphasized how GBV prevention can represent an entry point for CSE in contexts where sexuality may be difficult to talk about, and that CSE can contribute to various outcomes that support GBV prevention and response.

Challenges, Lessons Learned, and Promising Practices

Panelists went on to share their unique, diverse experiences working at the intersection of GBV and CSE. From the Philippines to Pakistan to Latin America and the Caribbean, they talked about challenges they face in their work and what they’ve learned along the way.

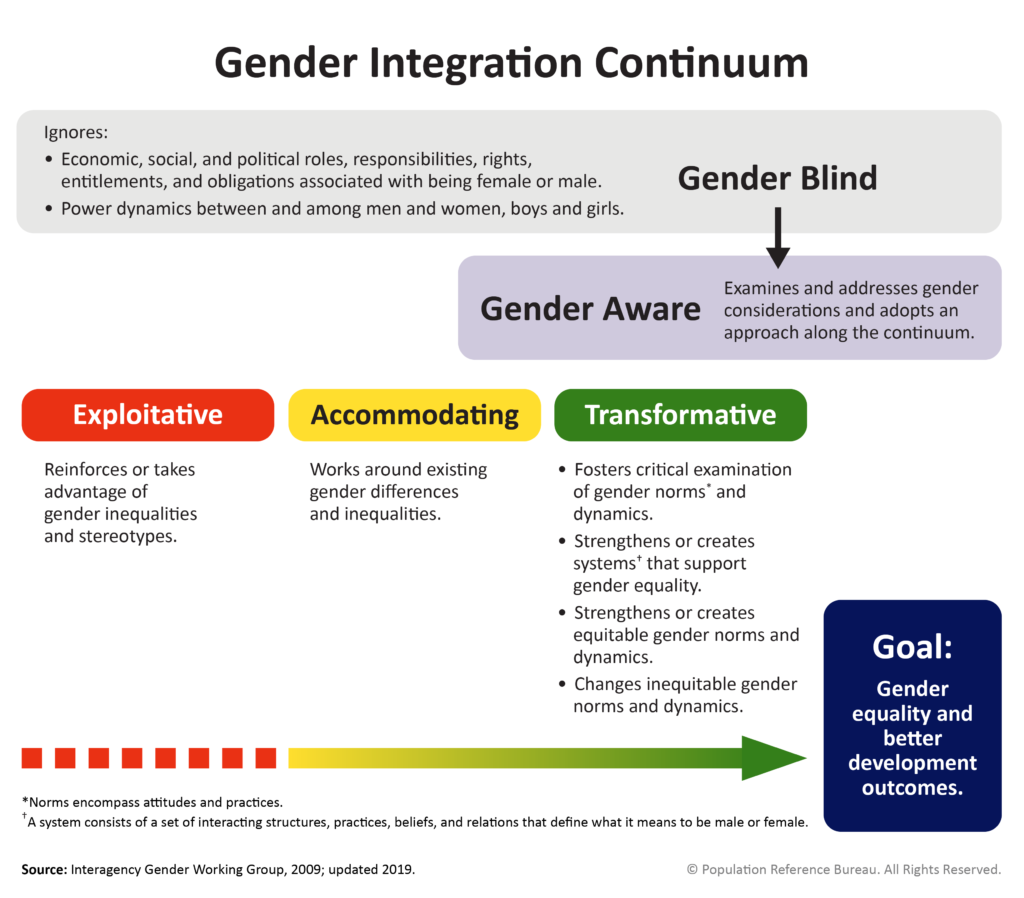

Sheena Hadi shared that in Pakistan, CSE is considered through the narrow lens of sexual behavior, focusing, for example, on preventing the transmission of sexually transmitted infections or on avoiding unintended pregnancy. Instead, the scope of CSE needs to be broadened to include topics like human rights, as well as skill development that can help challenge gender stereotypes. She also described how CSE should be taught to younger people, since power structures can be embedded at early ages. Other panelists agreed, emphasizing the importance of using gender transformative[i] approaches that work to shift harmful gender and social norms.

Shamah Bulangis said that in her context in the Philippines, teachers do not always have the support, training, or time to effectively incorporate CSE into their lesson plans. Addressing GBV tends to focus on response rather than prevention, with most efforts revolving around linking people to services rather than preventing violence in the first place. Silos between government departments like health and education, and even between local organizations in a particular context, can impede the work of integrating GBV and CSE, she said.

In addition to challenges, panelists provided insights on what they have learned through their work. Several touched on the need to prioritize a local approach during implementation, by working with and drawing on the leadership of community organizations who have a strong sense of the norms at play in the contexts in which they work. Even when there are relevant national laws and programs in place, there needs to be follow-through to ensure they are implemented. For example, in the Philippines, the Responsible Parenthood Reproductive Health Act of 2012 (Republic Act No. 10354) enshrines the role of the state in delivering age- and development-appropriate reproductive health education. The act clearly states the need for teachers to be trained to deliver this curriculum and specifically names GBV as a relevant subject to integrate into formal and nonformal educational systems, but gaps persist in its implementation. Grassroots and community organizations can help socialize laws with municipal governments and with school leaders, bridging the gap from passage to implementation.

Panelists agreed on the need for tools and methods that can be used to put international guidance into practice. Jeannie Ferreras Gómez highlighted the success of a UNFPA program that recently developed a toolkit, Cuatro pasos para prevenir la violencia basada en género: herramientas educativas para escuelas y comunidades (Four steps to prevent gender-based violence: Education toolkit for schools and communities) designed to address violence in schools and to support teachers and other leaders in Latin America and the Caribbean. Gómez shared insights about the comprehensive approach the toolkit takes on topics including human rights, gender and power, GBV, and gender and diversity.

Where to Go From Here

When asked about future opportunities for implementing CSE as part of GBV programming, panelists shared several recommendations for program implementers and funders. Their top suggestions included:

- Opportunities to integrate CSE with GBV should be explored through a whole-of-school-and-community approach that involves different interventions in and out of school. Teachers must be better supported to deliver CSE curricula, while also pursuing other innovative methods like using games and working with social media and community influencers who are critical to changing norms. Within the health system, bolstering efforts to make services adolescent-friendly offers another window of opportunity.

- Additional research is needed to better understand the links between receiving CSE and outcomes on education and health, as well as how CSE is contributing to violence prevention outcomes.

- Moving the needle requires program implementers—and funders—to take multi-sectoral approaches that break down silos between GBV and CSE as well as health, education, and other fields, mobilize grassroot actors, and form partnerships between organizations and movements working in the GBV and CSE spaces.

- Recognize that GBV can take different forms (physical, sexual, economic, or psychological harm) that require different solutions, and that programming must take these differences to heart.

- Program implementers should adopt context-specific approaches when designing and implementing GBV and CSE interventions, working with community members who are familiar with local social and gender norms, as well as ensure that CSE curricula are age- and development-appropriate.

Interested in learning more? The IGWG GBV Task Force welcomes you to check out the accompanying collection of CSE resources on FP insight.

This publication is made possible by the generous support of USAID through the PROPEL Health and Knowledge SUCCESS projects. This post was produced and prepared independently by the authors. The contents of this post are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

Endnotes

[i] Gender transformative policies and programs seek to transform gender relations to promote equality and achieve program objectives. This approach attempts to promote gender equality by 1) fostering critical examination of inequalities and gender roles, norms, and dynamics; 2) recognizing and strengthening positive norms that support equality and an enabling environment; 3) promoting the relative position of women, girls, and marginalized groups; and 4) transforming the underlying social structures, policies, and broadly held social norms that perpetuate gender inequalities.

References

- Goldfarb, Eva S. et al., “Three Decades of Research: The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education,” Journal of Adolescent Health, Volume 68, Issue 1, 13 – 27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.036. ↩︎

- Krug, E. G., Mercy, J. A., Dahlberg, L. L., & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083–1088. ↩︎

- Makleff, S., Garduño, J., Zavala, R.I. et al. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Among Young People—a Qualitative Study Examining the Role of Comprehensive Sexuality Education. Sex Res Soc Policy 17, 314–325 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00389-x ↩︎

- UNESCO. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education: An Evidence-Informed Approach. 2018. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260770. ↩︎

- UNFPA, Comprehensive Sexuality Education as a Strategy for Gender-Based Violence Prevention, 2021. https://mongolia.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/211129_unfpa_cse_report_v3_0.pdf ↩︎