The “IGWG Members Take the Mic” blog series intends to highlight lessons learned and best practices from and innovative approaches to gender transformative programming and research from IGWG members’ work and advocacy efforts to advance gender equality outcomes in global health. This blog is the second and final installment in this series. Read the first blog in the series exploring myths and misperceptions, social consequences, and crosscutting factors associated with reproductive agency and infertility here.

This blog post was authored by Thomas Sithole, Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Advisor, World University Service of Canada, Ghana; and Emah Udeme, Hub Coordinator, Youth Development and Empowerment Initiative, Nigeria.

Introduction

Gender transformative program work, or work that addresses root causes of gender inequalities, continues to encounter backlash at various levels of society, due to existing gender, power, and other sociocultural dynamics. In this blog, we discuss community backlash, or adverse reactions in communities, to male engagement interventions that utilize gender transformative[i] approaches to prevent gender-based violence (GBV) and promote sexual and reproductive health (SRH).

The authors each work on gender transformative male engagement interventions focused on GBV prevention and SRH promotion. In this blog, we draw on our experiences working with men and boys to promote more gender equitable norms and behaviors, including promotion of women’s rights and autonomy, within diverse settings and projects. We share examples of backlash from community members experienced by program participants and staff, how we have addressed them, and our actionable recommendations to other program implementers working in this space, including methods we have used to counter these reactions in ways that bring communities together.

What Is Backlash?

A recent journal article by Flood, Dragiewicz, and Pease defines backlash in the context of male engagement programming as “active resistance, opposition, or pushback against program efforts to build gender equality.”1 Backlash is a common response by dominant groups who feel threatened by challenges to their privilege and power by disadvantaged groups.2 A typical feature of backlash is the perception by some community members that structural gender inequality is acceptable.3 Backlash takes many forms, including denial of problems associated with gender inequality, disavowal of responsibility for the inequality, refusal to make changes that will benefit others, co-optation of program interventions in order to maintain structures of gender inequality (rather than dismantle them), and violence or threats of violence.4 It can also emerge as verbal abuse and ridicule or exclusion from social/peer gatherings. Anyone, regardless of gender identity, can face backlash for their positive stance on achieving gender equality.

Backlash can come from many sources, including media, community members, community and religious leaders, and family members and peers of program participants. In the context of gender transformative male engagement programming, backlash comes more often from men, who are members of the privileged group—especially community, cultural, and religious leaders and conservative men—than from women (the disadvantaged group), though women can also support patriarchal norms and contribute to this backlash. Backlash is also not limited to adults and adolescents.5 Some research shows that children are aware of gender norms, and are ready to sanction peers violating them, as young as the early preschool ages.6 Boys seem to be more likely to stereotype and to be sanctioned for not conforming.7

Such backlash can create barriers for all those participating in these programs —men, boys, women, girls, and gender-diverse people—and can hinder implementation. Yet many programs lack strategies to address it, creating a gap that can limit programmatic success. Understanding backlash and the context behind it enables program implementers to be better prepared and to develop strategies to prevent or respond to it.

There is limited research on the efficacy of interventions to address backlash. In our experience, when men and boys can work without fear of backlash, they may become more involved in efforts to promote gender equality; embrace positive and healthy forms of masculinity; promote women’s rights, health, and well-being; speak up against GBV; and contribute meaningfully to shifting harmful norms.

Introducing Our Program Settings

Thomas Sithole: My contributions to this blog come from my extensive work as a gender equality and social inclusion specialist and male engagement champion in many countries in Africa, including Botswana, Cameroon, Ghana, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. I also use insights from my work with the World University Service of Canada, which supports local partner organizations to address gender inequality and social exclusion through participatory, community-based interventions that raise awareness of violence against women and promote self-reflection and discussion. Our programs are rooted in values of inclusivity, collaboration, leadership, integrity, facilitation, and sustainability. Our strategies of engaging men and boys emphasize the importance of women’s rights, self-determination, and leadership, and situates the role of men and boys as allies of women. I also draw on my experiences with the Centre for Media Literacy and Community Development’s community engagement tool, a short film called Mukanya that has been particularly powerful in sparking productive dialogue about men’s role in perpetuating and preventing GBV. Use of a short film has made it easier for audiences to engage openly about their own reflections and experiences.

Emah Udeme: My professional journey has its foundation in working with adolescents in underprivileged communities in Nigeria. In my work in the field, I have come to understand their diverse and unique challenges and how adolescent boys and girls are affected by community backlash around gender equality. My contributions are drawn from my experiences working with the Youth Development and Empowerment Initiative (YEDI), a youth-centric organization committed to empowering young people that works with Development Alternative Incorporated (DAI), Grassroot Soccer, Yellow Brick Road, and the Women-Friendly Initiative on the Youth-Powered Ecosystem to Advance Urban Adolescent Health project. My role in the project is overseeing the operation of a youth hub that serves as a safe space for adolescent boys and girls. The goal of the project is to improve the SRH and well-being of urban, underprivileged, out-of-school, and unmarried adolescents in Kano and Lagos cities, Nigeria, by promoting voluntary contraceptive uptake, leadership, and livelihood skills. Grassroot Soccer’s signature SKILLZ model uses soccer games and participatory approaches to engage young people. In a typical SKILLZ session, a near-peer educator called a SKILLZ coach leads a group of 10 to 15 adolescents in discussions on various topics, including gender equity, positive masculinity, GBV, substance abuse, family planning, contraceptives, and anger management.

Where We’ve Seen Backlash in Our Work

Thomas: We have found that community backlash on what some perceive as dilution or adulteration of local culture can interrupt our program interventions. Those who support hegemonic masculinities [ii] feel that discussions on positive, progressive masculinities are an attack on their cultural norms and values. Verbal resistance often emerges in community dialogues, where some believe that gender equality is contrary to African cultures and an imposition from the West. For example, when our team was organizing screenings of Mukanya, we experienced backlash in the form of blockages to our planned interventions when some community and religious leaders refused to grant access to venues. The leaders denied venue access because they thought that the planned discussions about gender equality would have a negative influence on the members of the community. Eventually, we were forced to hold some gatherings under trees. In another example, in a recent community dialogue in Uganda, a village head objected to the actions of the program director facilitating the discussion because he allowed women to speak before men, which the village head felt was disrespectful to both men and local sociocultural norms—and perhaps a threat to his power. He demanded the meeting end early and forbade community members to attend similar future meetings, which demoralized the programming team.

Our work in Uganda has also indicated that backlash affects program staff and their families. Team members often face backlash from friends and community members, especially when discussing sensitive topics (such as same-sex relationships, which have been criminalized by law in Uganda) and where dialogues and debates can be emotionally and physically risky. Sometimes, staff can take the backlash personally. Sometimes, they fear for their safety, worried that they are exposing themselves and their families to threats and attacks. Backlash takes away their passion and energy and lowers morale.

Emah: In the SKILLZ program, we have noticed that backlash from the community leads to reduced participation in our sessions. In particular, boys who come from backgrounds of strongly established traditional gender norms fear stigma, ridicule, or ostracization, which can include being labeled as a “woman wrapper” (a derogatory local term in Nigeria implying a man controlled by women). SKILLZ participants who champion gender equality and positive and healthy masculinity reported experiencing different forms of backlash. A young man who plays in one of the community soccer teams reported that his stance on gender equity led to him being deemed too weak to play and pushed off his team by the manager—a decision that was later reversed when a SKILLZ coach intervened and sensitized the manager that males who advocate for gender equity are not weak, but are rather seeking ways to improve the lives of girls and women. To bypass such negative reactions, some young boys avoid participating or expressing support for gender equality.

Lessons Learned in Addressing Backlash

Thomas: Often in community dialogues, when people openly express resistance to gender equality, we have found that there is much power in letting them speak, no matter how controversial their views. Feeling heard can make them more open to alternative ideas. To counter the belief that gender equality is anti-African, we have found it productive to share examples of how culture changes over time. We also talk about powerful African men who have supported gender equality, like Rwandan President Paul Kagame and the late Kofi Annan, former UN Secretary General and a Ghanaian.

When planning community events, we engage proactively with those leading the backlash, including gatekeepers and opinion leaders, either individually or in groups, before the event (or afterward, as needed). When the situation is tense, we find it helpful to step back, regroup, and strategize. For example, we held a series of meetings with the village head in Uganda and other community leaders to explain the goal of our work and provide reassurance that we did not intend to threaten their leadership. We also emphasized the benefits of gender equality at the family and community levels, which included discussing how silencing women harms community progress.

To counteract the discouragement felt by program team members, we offer support by validating their efforts, highlighting achievements and small wins. We discuss our belief that backlash is a sign that their work is creating ripples of change, creating opportunities for dialogue, and engaging those who are resistant in conversations on men and gender equality.

Emah: To mitigate backlash, our programs engage with the community and families from the beginning. We invite community members to outreach activities or group discussions, which have helped build awareness of backlash, foster inclusive dialogue, establish partnerships, and promote ownership of the initiatives from the onset. Our program has specific outreach for parents of participants, including similar group discussions and information-sharing to address concerns and demonstrate the benefits of gender equality, health promotion, and violence prevention initiatives so that parents are more supportive. We seek feedback from parents, and have found that after discussing gender equality in the family, fathers are more likely to be present in future discussions.

We also equip participants with a deeper understanding of the context and the dynamics of backlash and how best to address it in their own lives and communities. The gender equality section in the SKILLZ curriculum focuses on its importance and how it benefits everyone to embrace it, as well as potential backlash and how to handle it. We encourage participants to get support from like-minded peers and to volunteer and collaborate with local influencers (such as movie actors and local artists who promote gender equality) in tackling backlash. We also link adolescent boys and girls who are survivors of GBV or who need further counseling with local organizations working on women’s rights issues for support and counseling. The Build Your Team session of the SKILLZ curriculum offers a key message: “Building our team of supporters can help us overcome obstacles and reach our goals in life.” It also includes short group-work activities to help participants identify their supporters and handle situations where they face backlash, encouraging open and honest discussions where they learn to communicate assertively and be resilient.

As one SKILLZ participant commented:

When my friends said I am stupid and not smart to allow my girlfriend to make decisions in my relationship, I just let them know that it works for me that way and that having a supportive girlfriend is also a good thing, and then I try to change the topic. Being a SKILLZ participant has taught me how to communicate assertively with confidence, and I use these skills to speak up against this backlash.

Recommendations for Program Implementers in Similar Settings

Informed by our experiences with Mukanya film screenings and the SKILLZ program, our joint recommendations for programmers implementing male engagement programming aimed at shifting inequitable gender norms and dynamics in SRH promotion and GBV prevention include:

- Know your audience and anticipate potential concerns. Ahead of community engagement activities, be informed on the relevant evidence on gender equality and practice your talking points. Consider which influential stakeholders may speak out in public or private, and plan how to engage.

- Communicate the rationale behind program goals and emphasize benefits to the communities, families, and individuals. Highlighting how programs are encouraging shared values and advancing progress can help counter misconceptions and resistance and show how existing norms and behaviors harm individuals, families, and communities.

- Engage adolescent boys and young men in safe, respectful, and supportive (formal or informal) learning sessions, offering space to discuss interconnected areas relevant to their lives (such as HIV, sexual violence and GBV, family planning, mental health, gender norms, and psychosocial support). To help anticipate and counter backlash, interventions should incorporate curriculum for adolescents that build awareness of social structures where backlash occurs (such as peer groups and religious or educational systems) and power relations (such as family dynamics or historical political trends) that affect them directly, help them to articulate their own views, and identify mentors and allies within their context, for greater support. Where available, link adolescents to groups working on women’s rights issues for services, such as counseling or psychosocial support, and opportunities to volunteer to help others experiencing backlash.

- Incorporate creative activities, like storytelling and sports, into programming. Such activities can mitigate the effects of backlash from family and friends by offering enjoyable and relatable entry points to the program and providing an opportunity to proactively discuss fears, doubts, and misconceptions. In particular, stories about fictional characters that feel true to the community’s lived experiences can help men and boys connect on neutral grounds.

- Proactively engage parents, gatekeepers, and cultural and religious leaders in discussions from the start, to address concerns and clarify intervention objectives. Ensuring that program goals and objectives are well understood can mitigate resistance from those who would have prevented or mobilized against it. Invite those who are curious or open to participating in your program interventions as members or allies. Where feasible, ask them to become change champions and ambassadors.

- Have conversations with community gatekeepers and opinion leaders who you believe are likely to create backlash. Frank discussions can help address fears and misconceptions. Once these individuals appreciate the benefits of progressive and healthy masculinities in their communities, they are more likely to be allies and to allow people to engage and participate freely.

- Encourage open debate in discussions with communities, and listen without becoming defensive. A program facilitator’s skill in setting the tone and managing debate in community dialogues is key. A program facilitator should allow people to speak their views, and then provide alternative scenarios or framing. After hearing one person’s perspective, a good facilitator can invite others in the room to share an alternative viewpoint, to reinforce the perception that there is not just one universal opinion in the community. It helps for the facilitator to acknowledge people’s fears and misinformation about gender equality and perceived loss of privilege and power, and offer a reframing that emphasizes shared values. One way to challenge myths and other contributing factors to backlash is to lead with the facts, before debunking the myth.

- Offer regular capacity strengthening and support to project staff and program participants. This can include counseling services for those experiencing backlash. Provide strategies for understanding and dealing with backlash and its effects on program participants, families, and community members. When facing intense backlash, step back, regroup, and strategize about what steps to take next. Share practical tips for mitigating and addressing backlash, based on program interventions or specific contextual realities. Implement routine backlash monitoring processes like pulse checks and feedback loops from community leaders, community members, parents, and other key stakeholders such as groups working to advance women’s rights and gender equality to identify emerging issues or trends and potential solutions.

- In mitigating backlash, engage in supportive partnerships and collaborations with women’s rights organizations. When working with them, men’s engagement programs should guard against taking over and dominating the space. Listen to women’s voices in a way that inspires trust and respect. Ask women’s rights groups how male engagement programming can amplify efforts to promote gender equality and mitigate backlash.

- Recognize that backlash can be a sign that program implementation efforts are gaining traction. Long-term change is made up of small achievements that should be celebrated along the way. Even though backlash can discourage and demoralize program teams at times, program teams can take comfort in knowing that backlash is a sign that the program is helping to address and transform social norms that perpetuate gender inequality.

Conclusion

Backlash is a common challenge for program implementers working to address root causes of gender inequalities and inequitable power dynamics while engaging men and boys in GBV prevention and SRH promotion interventions. Program implementers need to be prepared and have strategies in place for responding to or preventing backlash. This calls for solutions that require understanding the various dynamics and forms of backlash (including the cultural context and relevant gender norms), the key players behind them, and a careful crafting of response and mitigation measures with key stakeholders. By addressing backlash, program implementers can strengthen male engagement programs and better support and empower men and boys, women and girls, and their partners to take steps toward breaking free from harmful gender norms and advancing gender equality.

Acknowledgments

This blog was written by Thomas Sithole (based in Ghana) of World University Service of Canada and Emah Udeme of Youth Development and Empowerment Initiative in Nigeria. The authors would like to thank Francesca Alvarez and Cathryn Streifel of the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) and Doris Bartel, independent consultant for their review and contributions to the blog. The authors would also like to thank Courtney McLarnon and Dominick Shattuck for their review on behalf of the IGWG Male Engagement Task Force and suggestions for strengthening. Finally, the authors would also like to express gratitude to Afeefa Abdur-Rahman of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) for her valuable technical guidance and support with the development of this blog.

This publication is made possible by the generous support of USAID under cooperative agreement 7200AA22CA00023. This post was produced and prepared independently by the authors. The contents of this post are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Endnotes

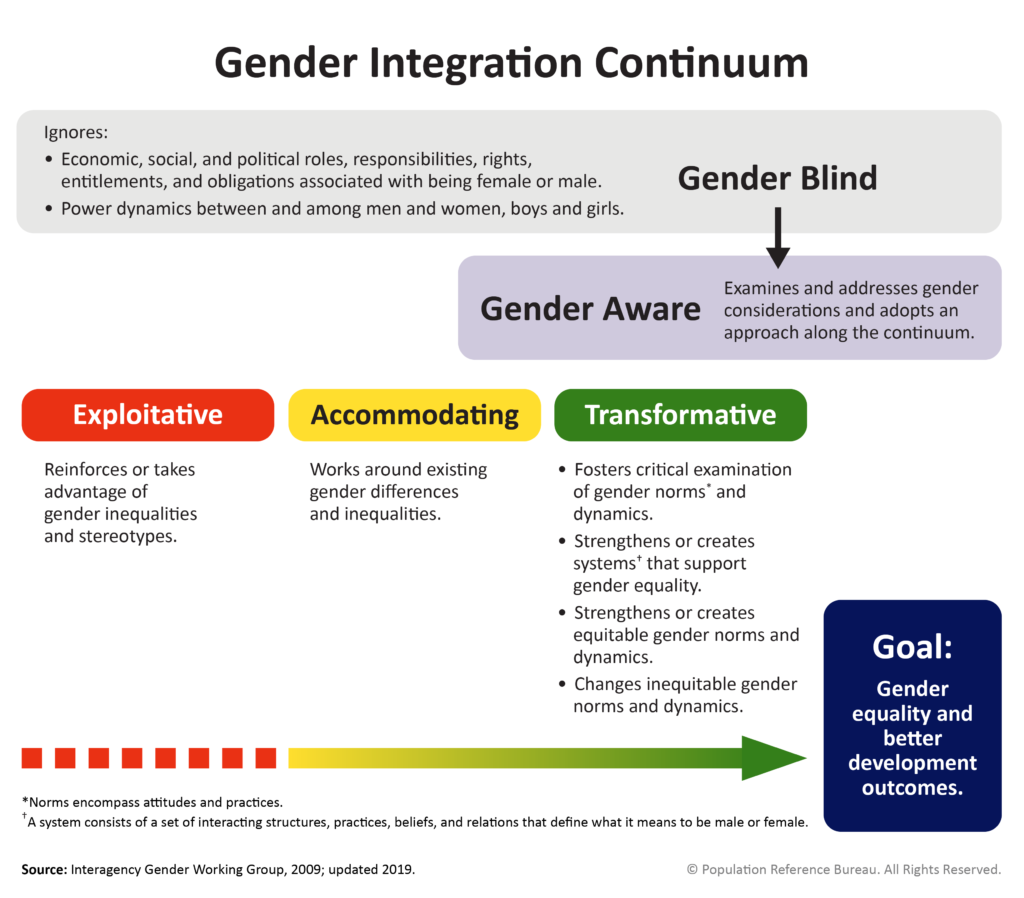

[i] Gender transformative policies and programs seek to transform gender relations to promote equality and achieve program objectives. This approach attempts to promote gender equality by 1) fostering critical examination of inequalities and gender roles, norms, and dynamics; 2) recognizing and strengthening positive norms that support equality and an enabling environment; 3) promoting the relative position of women, girls, and marginalized groups; and 4) transforming the underlying social structures, policies, and broadly held social norms that perpetuate gender inequalities.

[ii] Drawing from Connell and Messerschmidt’s Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept (2005), we define hegemonic masculinity/ies as cultural conceptions of multiple masculinities, ordered in hierarchies associated with social power, that reinforce domination over subordinate groups, often reinforcing rigid conceptions of idealized forms of masculine and feminine characteristics.

References

- Flood, M., M. Dragiewicz, and B. Pease. 2021. “Resistance and Backlash to Gender Equality.” Australian Journal of Social Issues 56 (3): 393-408. ↩︎

- Blais, M. and F. Dupuis-Déri. 2012. “Masculinism and the Antifeminist Countermovement.” Social Movement Studies 11 (1): 21-39. ↩︎

- Flood, Dragiewicz, and Pease, 2021, “Resistance and Backlash.” ↩︎

- Flood, Dragiewicz, and Pease, 2021, “Resistance and Backlash.” ↩︎

- Flood, M., M. Dragiewicz, and B. Pease. 2018. “Resistance and Backlash to Gender Equality: An Evidence Review.” ↩︎

- Skočajić, M.M., J. G. Radosavljević, M. G. Okičić, I. O. Janković, and I. L. Žeželj. 2020. “Boys Just Don’t! Gender Stereotyping and Sanctioning of Counter-Stereotypical Behavior in Preschoolers.” Sex Roles 82: 163-172. ↩︎

- Sullivan, J., C. Moss-Racusin, M. Lopez, and K. Williams. 2018. “Backlash Against Gender Stereotype Violating Preschool Children.” PloS one 13(4): e0195503. ↩︎