This blog post was written for the Interagency Gender Working Group’s (IGWG) Gender-Based Violence (GBV) Task Force by Sophie Read-Hamilton, with support from Alyssa Bovell, Emily Clark, Joy Cunningham, and Francesca Alvarez.

Digital technology is an essential tool for global development, with tremendous potential for accelerating gender equality, women’s rights, and health outcomes, including sexual and reproductive health (SRH). There are numerous examples of information and communication technologies (ICTs) being harnessed to address barriers to access and the provision of SRH services.[1] However, as well as opportunities, technology presents us with challenges. One of the most concerning challenges is the rise of technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV). TFGBV, also called online violence, cyber violence, and digital violence, includes all forms of GBV committed using ICTs, including mobile phones, smartphones, the internet, social media, or other digital platforms or tools. The misuse of technology can have devastating consequences for women and girls’ safety, health, and rights when it is used to intimidate, harass, exploit, abuse, stalk, threaten and blackmail. To mitigate misuse of and capitalize on the potential that digital technology offers for accelerating universal access to SRH services, it is critical that SRH practitioners, services, and programs understand and address TFGBV.[2]

What Is TFGBV?

TFGBV includes violence that occurs in online spaces and violence perpetrated offline through technological means. It encompasses a range of behaviors, including online harassment, non-consensual sharing of intimate images (sometimes called revenge porn), sextortion (threatening to publish sexual information or coercing an individual into a sexual activity through blackmail or threats), stalking, hate speech, and threats made through digital channels.[3] Technology can also be used to exacerbate or perpetrate offline violence against women and girls. For example, perpetrators of intimate partner violence may use mobile phones, GPS, and tracking devices to intimidate and control victims.[4] As another example, sex traffickers use technology to profile, recruit, control, and exploit victims.[5]

Who Is at Risk?

All women—across the globe—with access to digital technology are at risk of TFGBV. Some women are more likely to experience it because of what they do or who they are. [6] Reports show that women with intersectional identities based on race, ethnicity, ability, caste, sexual orientation, or gender identity face higher rates of online harassment and attacks.[7] Age is also a risk factor for TFGBV, with adolescent girls and young women particularly vulnerable to sexual harassment, abuse, and exploitation perpetrated using mobile phones and social media. A global study by Plan International in 32 countries found 58% of adolescent girls had experienced harassment on social media platforms.[8] The same study found 42% of girls and young women who self-identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer; 14% of those who self-identify as having a disability, and 37% of those who self-identify as belonging to an ethnic minority, reported experiencing online harassment relating to these characteristics. TFGBV is also one of the key tactics used to threaten women human rights defenders and is often a precursor to physical violence.[9]

As more women and girls around the world access mobile phones and the internet, more will be exposed to violence perpetrated through technology by a wide range of people, including current and former partners, acquaintances, and strangers. A study by the Economist Intelligence Unit looking at perpetrated TFGBV among adult women in 51 countries found:[10]

- 38% of all women reported personal experiences with online violence.

- 45% of younger women ages 18 to 30 had experienced online violence.

- 65% reported knowing other women who had been targeted online.

- 85% reported witnessing online violence against other women.

Characteristics of TFGBV

Whether TFGBV is an extension of in-person GBV or is limited to the digital realm, there are characteristics that make it different from in-person violence. These characteristics influence how survivors are affected. For example, TFGBV can be:

- Perpetrated anonymously, across geographical locations: Perpetrators can enact abuse from anywhere in the world, even when not in physical proximity, making it very difficult to identify and stop perpetrators or hold them accountable.

- Easily perpetrated using low-cost technology and with limited skill, time, and effort.

- Perpetrated with impunity: Abusers and perpetrators often escape any form of punishment or accountability.

- Perpetrated by multiple individuals, including primary perpetrators, as well as secondary perpetrators, who download, forward, or share violent or abusive content.

- Perpetrated in the public domain, unlike offline GBV (which is generally done in private), amplifying the exposure of this form of violence and its impacts and harms.

- Long term, with abusive content potentially existing indefinitely due to the ease of replication. Abusive text and images can be copied and moved to different platforms or sites and be impossible to delete. This can result in future and recurring victimization or traumatization.

TFGBV has serious and long-lasting impacts for individuals, communities, and wider societies. This includes the silencing of women, also referred to as the ‘chilling effect’ on women’s public and democratic participation, which, for example, may impact women’s and girls’ political ambitions and engagement in public and political spaces.[11] It also threatens to rollback women’s and girls’ rights and advancements in gender equality by restricting their online activity and inhibiting their access to the internet, a critical economic, social, and political resource in the digital age, increasing the digital gender divide and restricting women’s voices and rights to public participation. Individuals targeted by perpetrators of TFGBV can experience sexual, physical, emotional, psychological, social, and economic harm.

Connections Between TFGBV and SRHR

While research on the relationship between TFGBV and sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) is still in its infancy, there are some clear connections.

- Survivors of TFGBV often experience severe emotional, psychological, and social harms, which can significantly influence their sexual and reproductive health and choices. For example, the mental health effects of image-based sexual abuse can be similar to symptoms experienced by survivors of offline sexual abuse. [12] This type of trauma may lead to anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and diminished sense of agency in decision-making about sexual and reproductive health (SRH), affecting intimate relationships, contraception decisions, and access to reproductive health.[13]

- TFGBV is commonly linked with in-person GBV and may therefore exacerbate harmful SRH consequences for those experiencing multiple forms of GBV.[14] For example, technology may be used as a tool of reproductive coercion by perpetrators of intimate partner violence (IPV).[15] Perpetrators of IPV and sexual exploitation may use digital surveillance, tracking, and threats, making it challenging for victims to access SRHR information and resources safely.

- TFGBV can inhibit women and girls from using technology, potentially reducing their access to SRHR information and services. Those already directly targeted by or a witness to TFGBV often withdraw from online engagement, platforms, and services.[16] Fearful of TFGBV, families may limit girls’ and women’s access to technology. In this way, TFGBV can prevent women and girls from seeking SRHR information and services. This can result in reduced access to family planning, contraceptives, and sexually transmitted infection testing and treatment.

- TFGBV is used as a tactic to silence and shut down organizations and individuals promoting SRHR. TFGBV may be used to surveil women’s organizations advocating for or providing SRH services, including those procured online.[17] Advocates defending women’s rights, such as reproductive rights, face doxing, online threats, and intimidation and harassment. [18] Young women and adolescent girls who speak out online about political issues, feminism, race, or SRHR face considerable backlash.[19]

- TFGBV reinforces harmful gender norms linked to poor SRHR outcomes. For example, the online dissemination of degrading messages about women or girls, violent and hypersexualized images, and the expectations about women’s and men’s sexuality and roles reinforce harmful norms about women’s sexual autonomy that sustain gender power hierarchies and male control over women’s sexuality. Inequitable norms about gender and power also influence women’s sexual and reproductive choices and rights, such as the ability to independently and freely make decisions regarding if and when to use contraception and which methods to use.[20]

Recommendations for SRH Practitioners, Services, and Programs

Efforts to address TFGBV are evolving, and promising global initiatives and partnerships are emerging. This includes the Global Partnership for Action on Online Gender-Based Harassment and Abuse, which is bringing together countries, international organizations, civil society, and the private sector to better prioritize, understand, prevent, and address TFGBV.[21] A TFGBV research priority agenda is being developed to bolster efforts to generate evidence to address the issue. UN agencies are developing guidance and resources to make technology safer for women and girls. [22] Organizations such as the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) have a long history of advocacy and actions to address TFGBV and continue their work, joined in these efforts by many women’s and digital rights organizations in the Global South. [23]

Despite this progress, there is currently very limited research and attention on the relationship between TFGBV and SRHR. While researchers are starting to look more closely at the intersection between technology, GBV, and SRH, the area is still underexplored, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.[24] Until more evidence is produced and can be used to identify best practice approaches for SRH practitioners, services, and programs to address TFGBV in different contexts, the following minimum strategies should be considered:

- Build awareness about the issue of TFGBV among SRH services and users. SRH services are well-placed to provide information to service users and the wider community on TFGBV. Education should focus on risks, digital safety, consent, healthy relationships, and gender equality to empower individuals to navigate the digital world safely. Raising awareness about TFGBV and its intersection with SRHR is essential.

- Integrate TFGBV prevention and response into new and existing SRH programming. For example, SRH services and practitioners are well-placed to support survivors who disclose experiences of TFGBV to them. Seek opportunities to build the capacity of SRH staff to respond to TFGBV disclosures and ensure that survivors have access to appropriate care and assistance.

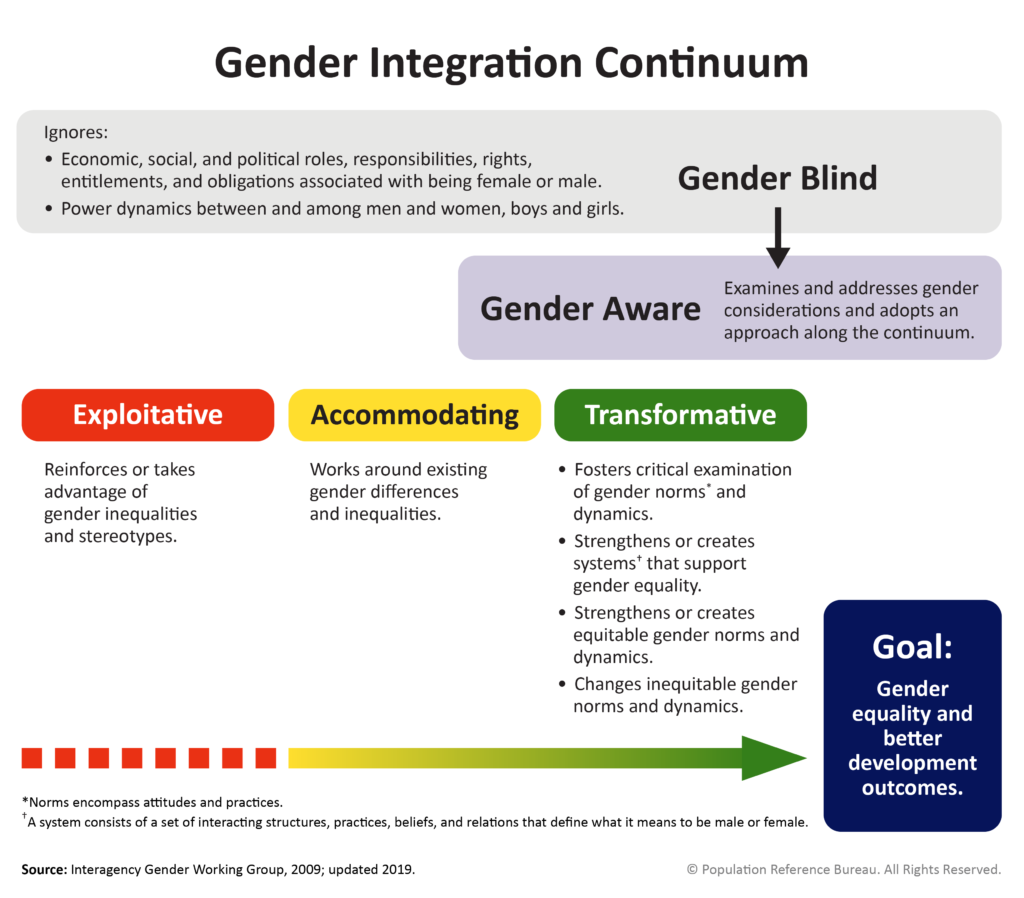

- Redouble efforts to promote gender equality and healthy social norms to help prevent all forms of GBV and support positive SRH outcomes. Context-specific gender-norms change programming should aim to reach individuals across social groups and be inclusive of those from diverse backgrounds and identities based on age, race, ability, caste, etc. Programming should include—but not be limited to—discussions on gender equality, respecting boundaries and consent, and SRH education. These programs can be introduced in schools and workplaces, as well as directly into the community, by both SRH and GBV programs.

- Build privacy and safety by design into digital SRH services and innovations to safeguard against TFGBV. SRH programs and services that are harnessing digital tools must adopt emerging good practice in digital design in SRH programs and for anticipating, detecting, and eliminating online harms before they occur. [25]

- Advocate with donors to invest in and partner on research on the intersection between TFGBV and SRHR. There is a critical need to generate information and knowledge about TFGBV and its links to SRH and to generate evidence on effective strategies for programming and interventions at this intersection.

- Partner with allies working in women’s and digital rights to collectively advocate for action on TFGBV by online industries and social media companies at national and regional levels. Work collaboratively to engage technology companies and pressure them to take greater responsibility for preventing harassment, threats, intimidation, and the incitement and perpetration of GBV through their platforms, and create safer online communities for all users.

The intersection of TFGBV and SRHR is a deeply concerning issue that demands immediate attention.

By fostering a safe digital environment and implementing comprehensive prevention and response, we can work toward a world where technology empowers rather than endangers individuals and serves as a tool to advance gender equality and the realization of SRHR for all.

This publication is made possible by the generous support of USAID through the PROPEL Health and Knowledge SUCCESS projects. The contents of this post are PROPEL Health and Knowledge SUCCESS’s sole responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

References

[1] World Health Organization (WHO), HRP at 50: Harnessing the Power of Science, Research, Data and Digital Technologies to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (2023), https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073838.

[2] WHO, “SDG Target 3.7 Sexual and Reproductive Health,” Global Health Observatory, https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/sdg-target-3_7-sexual-and-reproductive-health.

[3] UNFPA, “Digital Violence Terms,” https://www.unfpa.org/thevirtualisreal-background#glossary.

[4] Eva PenzeyMoog and Danielle C. Slakoff, “As Technology Evolves, so Does Domestic Violence: Modern-Day Tech Abuse and Possible Solutions,” in The Emerald International Handbook of Technology-Facilitated Violence and Abuse, edited by Jane Bailey, Asher Flynn, and Nicola Henry (Emerald Publishing Limited, 2021), https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/978-1-83982-848-520211047/full/html.

[5] Human Trafficking Front, “Social Media and Child Sex Trafficking,” https://humantraffickingfront.org/social-media-and-child-sex-trafficking/.

[6] Julie Posetti et al., The Chilling: Global Trends in Online Violence Against Women Journalists (UNESCO, 2021), https://en.unesco.org/publications/thechilling.

[7] Council of Europe, The Digital Dimension of Violence Against Women as Addressed by the Seven Mechanisms of the EDVAW Platform (2022), https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/cedaw/statements/2022-12-02/EDVAW-Platform-thematic-paper-on-the-digital-dimension-of-VAW_English.pdf.

[8] Sharon Goulds, et al., State of the World’s Girls 2020: Free to Be Online? Girls’ and Young Women’s Experiences of Online Harassment (Plan International, 2020), https://www.plan.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SOTWG-Free-to-Be-Online-2020.pdf.

[9] Maia Kahlke Lorentzen, et al., Online Harassment and Censorship of Women Human Rights Defenders (DanChurchAid, 2023) https://www.danchurchaid.org/report-online-harassment-and-censorship-of-women-human-rights-defenders#:~:text=Of%20the%2012%20female%20human,instead%20of%20doing%20their%20work.

[10] “Measuring the Prevalence of Online Violence Against Women,” The Economist Intelligence Unit, March 1, 2021, https://onlineviolencewomen.eiu.com/.

[11] Amrita Vasudevan, “Beyond Difference: Understanding the Chilling Effects of Technology-Facilitated Gender Based Violence,” GenderIT.org, March 23, 2023, https://genderit.org/feminist-talk/beyond-deterrence-understanding-chilling-effects-technology-facilitated-gender-based#:~:text=In%20addition%20to%20the%20invasion,’chilling%20effect’%20on%20speech; PACT and IREX, “More than a Women’s Rights Issue: How Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence Is a Threat to Democracy,” recording of webinar on April 12, 2023, https://www.pactworld.org/library/more-womens-rights-issue-how-technology-facilitated-gender-based-violence-threat-democracy; and Kirsten Zeiter, et al., Tweets That Chill: Analyzing Online Violence Against Women in Politics (National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, 2019), https://www.ndi.org/tweets-that-chill.

[12] Clare McGlynn, et al., “‘It’s Torture for the Soul’: The Harms of Image-Based Sexual Abuse,” Social & Legal Studies 30, no. 4: 541-62, https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663920947791; and “Image-Based Sexual Abuse: An Introduction,” EndCyberAbuse.org, https://endcyberabuse.org/law-intro/.

[13] Antoinette Huber, “‘A Shadow of Me Old Self’: The Impact of Image-Based Sexual Abuse in a Digital Society,” International Review of Victomology 29, no. 2: 199-216, https://doi.org/10.1177/02697580211063659.

[14] University of Melbourne and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Measuring Technology: Facilitated Gender-Based Violence. A Discussion Paper (2023), https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/UNFPA_Measuring%20TF%20GBV_%20A%20Discussion%20Paper_FINAL.pdf.

[15] “Reproductive Coercion and Technology,” Safety Net Project, National Network to End Domestic Violence, https://www.techsafety.org/reprocoercion.

[16] International Telecommunications Union, “Women’s Safety Online: A Driver of Gender Inequality in Internet Access,” May 21, 2020, https://www.itu.int/hub/2020/05/womens-safety-online-a-driver-of-gender-inequality-in-internet-access/.

[17] University of Melbourne and UNFPA, Measuring Technology: Facilitated Gender-Based Violence. A Discussion Paper. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/UNFPA_Measuring%20TF%20GBV_%20A%20Discussion%20Paper_FINAL.pdf

[18] AccessNow, “Silenced, Spied on, and Stalked: Why We’re Taking the Fight for Gender Equality to the UN,” March 6, 2023, https://www.accessnow.org/silenced-spied-on-and-stalked-why-were-taking-the-fight-for-gender-equality-to-the-un/; and “The Impact of Online Violence on Women Human Rights Defenders and Women’s Organisations: Statement by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein,” United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner, 38th session of the Human Rights Council, June 21, 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2018/06/impact-online-violence-women-human-rights-defenders-and-womens-organisations.

[19] Alexandra Robinson and Nora Piay-Fernandez, Making All Spaces Safe: Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence (UNFPA, 2021), https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/UNFPA-TFGBV-Making%20All%20Spaces%20Safe.pdf

[20] Brittany Goetsch, “What Impact Do Gender and Power Have on FP Decision-Making?,” Knowledge SUCCESS, Jan. 26, 2022, https://knowledgesuccess.org/2022/01/26/what-impact-do-gender-and-power-have-on-fp-decision-making/?hilite=gender+equality.

[21] U.S. Department of State, “2023 Roadmap for the Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse: Fact Sheet,” March 28, 2023, https://www.state.gov/2023-roadmap-for-the-global-partnership-for-action-on-gender-based-online-harassment-and-abuse/.

[22] UNFPA, Guidance on the Ethical Use of Technology to Address Gender-Based Violence and Harmful Practices: Implementation Summary (2023), https://www.unfpa.org/publications/implementation-summary-safe-ethical-use-technology-gbv-harmful-practices; and Laaha, a Virtual Safe Space for Women and Girls, https://laaha.org/country-selector.

[23] Association for Progressive Communications, https://www.apc.org/; and Take Back the Tech: Take Control of Technology to End Gender-Based Violence, https://www.takebackthetech.net/.

[24] Keng-Yen Huang et al., “Applying Technology to Promote Sexual and Reproductive Health and Prevent Gender Based Violence for Adolescents in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Digital Health Strategies Synthesis From an Umbrella Review,” BMC Health Services Research 22 (2022), https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-022-08673-0.

[25] Loraine J. Bacchus, et al., “Using Digital Technology for Sexual and Reproductive Health: Are Programs Adequately Considering Risk?,” Global Health: Science and Practice 7, no. 4 (2019): 507-14, https://doi.org/10.9745%2FGHSP-D-19-00239; eSafety Commissioner, Australian Government, “Safety by Design,” https://www.esafety.gov.au/industry/safety-by-design.