To commemorate the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence (GBV), Stephanie Perlson and Rose Wilcher, co-chairs of the GBV Task Force of USAID’s Interagency Gender Working Group caught up with Gary Zeitounalian, gender program technical support with ABAAD Resource Center for Gender Equality in Lebanon, and with Wangechi Wachira, executive director at the Centre for Rights Education and Awareness (CREAW) in Kenya, to learn how they are adapting their programming to address the violence prevention and response needs of women and girls during the COVID-19 pandemic. Presented in two parts, these interviews offer practical insights and inspiration from program implementers and advocates on the front lines.

A Conversation With Wangechi Wachira, Centre for Rights Education and Awareness

Can you briefly describe CREAW’s work with women and girls to address GBV and other reproductive health issues?

At CREAW, we work across Kenya, seeking holistic approaches to promote gender equality, women’s and girls’ full participation and empowerment, and their economic and social justice, along with preventing and responding to violence against women and girls (VAWG) and eliminating harmful practices such as child, early, and forced marriages (CEFM) and female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C). We also work to support women and men to transform social norms and practices on maternal and newborn health (MNH) and reproductive health (RH) along with facilitating community access to the services. We aim to address the barriers that inhibit women’s and girls’ RH, such as discrimination against users and providers of RH care. Creating this enabling environment has led to improved gender responsive MNH, menstrual hygiene, and RH care at both the community and county levels.

What are some of the most urgent GBV and reproductive health needs of women and girls that you’ve observed or heard about during the COVID-19 pandemic?

With COVID-19, we’ve seen that GBV service delivery and access to MNH, RH, menstrual hygiene management, and mental health services, as well as justice services are most urgent. Also, families have lost their income, so domestic violence increased, due to the economic stress caused by lockdowns. Cases of GBV reported on our toll-free helplines increased substantially, from a few cases per day to an average of 90 cases per month. In April, the National Council on Administration of Justice came out saying that GBV rates were increasing by 35 percent. We asked ourselves: “What are the pathways to address the cases?” Courts were closed, so access to legal support has been a challenge. Teen pregnancy has also become a more urgent issue; the economic and health crises caused by COVID-19, prolonged school closures, and movement restrictions resulted in coercion, rape, and/or transactional sex. With stay-at-home orders, many adolescent girls and young women cannot access the health services they need, and for women and girls experiencing violence, they are locked up with perpetrators and cut off from people and resources they need to help them.

How is CREAW trying to help address those needs?

Given COVID-19 guidelines, we have a created toll-free helpline for women and girls to get psychosocial support, legal aid, and referrals to other GBV service providers. CREAW advocated for more government resources for GBV prevention and response and for referrals for women and girls to get GBV and psychosocial support services. To address survivors’ RH needs, we refer them to medical facilities and health care providers where RH care, including post-rape care, are offered. Also, we support six shelter homes and safe spaces for women and girls throughout the country and are onboarding additional shelters identified across the counties where we have a presence. Unfortunately, there is only one government run shelter; the rest are donor-supported. We reached out to UN Women and Mastercard Foundation to get additional support for the shelters and re-directed some of our funding so that they had the resources they need to assist women and girls. These shelters also support girls escaping child marriages and pregnant teens. Shelters use the sub-grants for operational costs, as well as food, counselors, and dignity kits. Women come to shelters with their children, so the shelters provide for them, too. CREAW also supports nascent women’s organizations, who help to identify women and girls needing GBV services.

To cushion families, CREAW also started to carry out cash transfers with the support of Oxfam, Kenya Red Cross, European Union, Denmark in Kenya Mastercard Foundation, African Women Development Fund, and the United Nations Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women, looking at the cost of a food basket each month. For the past month, we have provided a cash transfer for each survivor to get a food basket, and we’ve reached over 4,583 survivors in Nairobi, Mombasa, Isiolo, Kilifi, and Narok Counties.

Certainly, violence against women and girls was a major global concern before the COVID-19 pandemic. What are some of the ways in which CREAW has had to adapt its GBV programming in light of COVID-19, and what strategies seem to be working well?

We typically use the SASA! model of community dialogues, but this has been difficult with COVID-19 restrictions. So, we developed key GBV prevention and response messages targeting survivors, women and girls, and duty bearers and started using social media platforms, community radios, and community leaders to disseminate them. For survivors, the messages explained where to get services such as the toll-free helpline, health services, and shelter, for example. To address FGM/C and CEFM during the pandemic, we are working with women-led groups, gender activists, and local administration at the community level to spear head community conversations/actions. We also worked with the Prevention Collaborative to adapt our community dialogue approach by using virtual platforms. Previously, we worked one-on-one with clients at the CREAW office, but now we support clients virtually, within the COVID-19 protocols. For women with little or no access to technology, we have leveraged our local program officers and other local women’s groups across the country to identify GBV survivors and connect them with cash transfers and other essential support. With courts operating virtually and digital accessibility challenges, we had to re-organize and devise how to get survivors legal representation in court, and how women could access it, when there are challenging circumstances. For example, you need to have an email address for court hearings, so we had to find ways for lawyers to meet with them. Therefore, in Kibera, we set up a room for a lawyer to meet one on one with survivors. In counties with no lawyer, we have set up pro bono lawyers network to provide legal assistance.

What advice do you have for policymakers who have an obligation to protect women and girls during the pandemic?

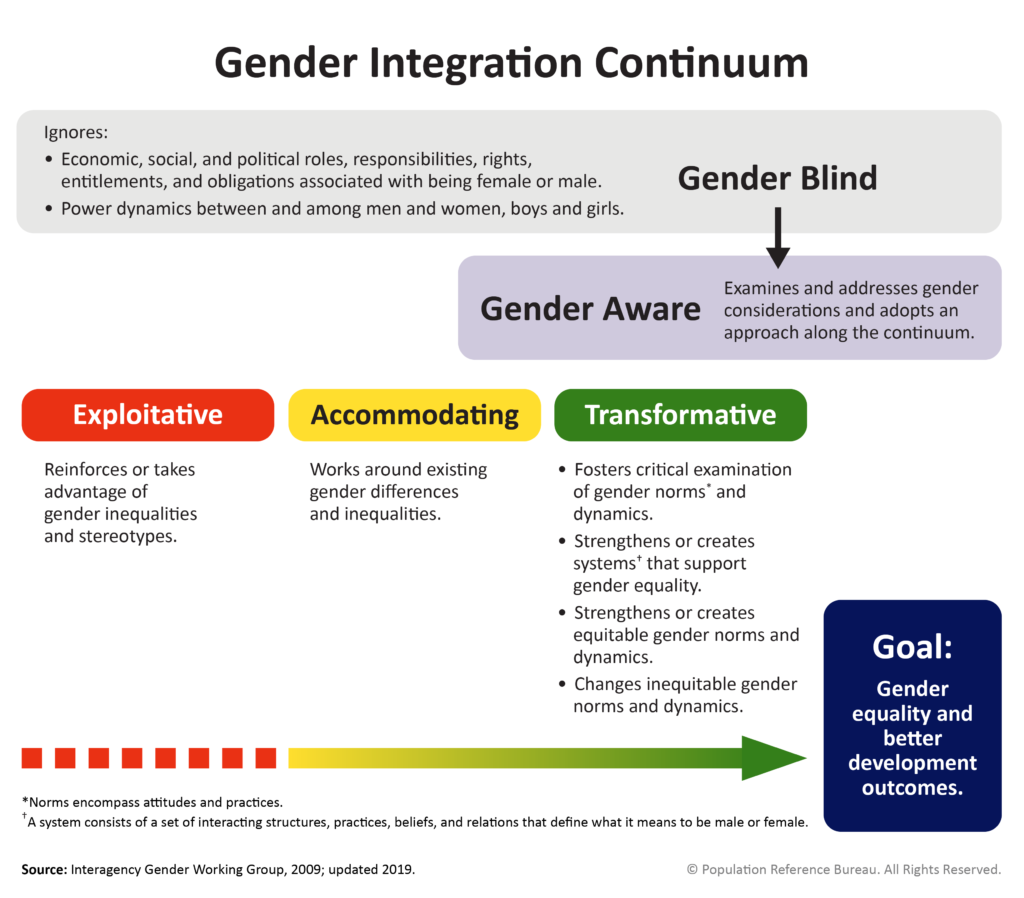

They need to fully implement GBV policies for accountability; increase budgetary allocation to GBV prevention and response programs so that survivors can access essential health services, such as psychosocial support, MNH, and RH; and invest in safe houses and shelters for women and girls. Most GBV prevention work is driven by NGOs, therefore, the state needs to take up GBV prevention work—implementing programs and policies to help change gender norms and other forms of discrimination that lead to GBV and poor RH outcomes—so it can be funded and scaled up. They need to strengthen accountability throughout the criminal justice system, from police and up. For example, police are deployed to deal with curfews, so they can serve as the front line to address GBV cases. Within the criminal justice system, it takes too long for cases to be processed. The justice system should establish special courts that focus exclusively on addressing cases of sexual violence so that they are handled more quickly. Lastly, in Kenya, social protection primarily focuses on the elderly, but GBV survivors should fall under this mandate, too.

What are your top two or three pieces of advice for implementers who are working to prevent violence against women and girls or provide effective support to survivors right now?

Implementers need to work on coordination with each other and data management. At the national level, coordination happens. But better coordination is needed at the county level—among police, CSOs, county government, judiciary, and the Office of Director of Public Prosecutions—to ensure that the referral pathway is clear so that survivors can access the GBV, health, and legal services they need. In Kenya, there is a gender technical working group at county level; they all need to work together and ask, “What are the data telling us? What is working to prevent and respond to GBV?” Also, more work needs to be done on survivor resilience, such as providing supportive structures for survivors to build their economic empowerment as they reorganize their lives and how to make programs sustainable beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Is there a “silver lining” thought related to how COVID-19 has shaped the world for women and girls that you’d like to share?

COVID is the perfect storm to be able to see everything we’ve worked on and for pointing out what is still needed. It’s provided an opportunity at all levels—from the local to the national level—to catalyze service provision for women and girls. We have seen development partners willing to listen and put the money where it’s needed. The pandemic is giving us the opportunity to “fund, respond, prevent collect!”

For more information and resources from CREAW on addressing GBV during the COVID-19 pandemic, please visit: https://home.creaw.org/publications/.

Some resources you’ll find there include: